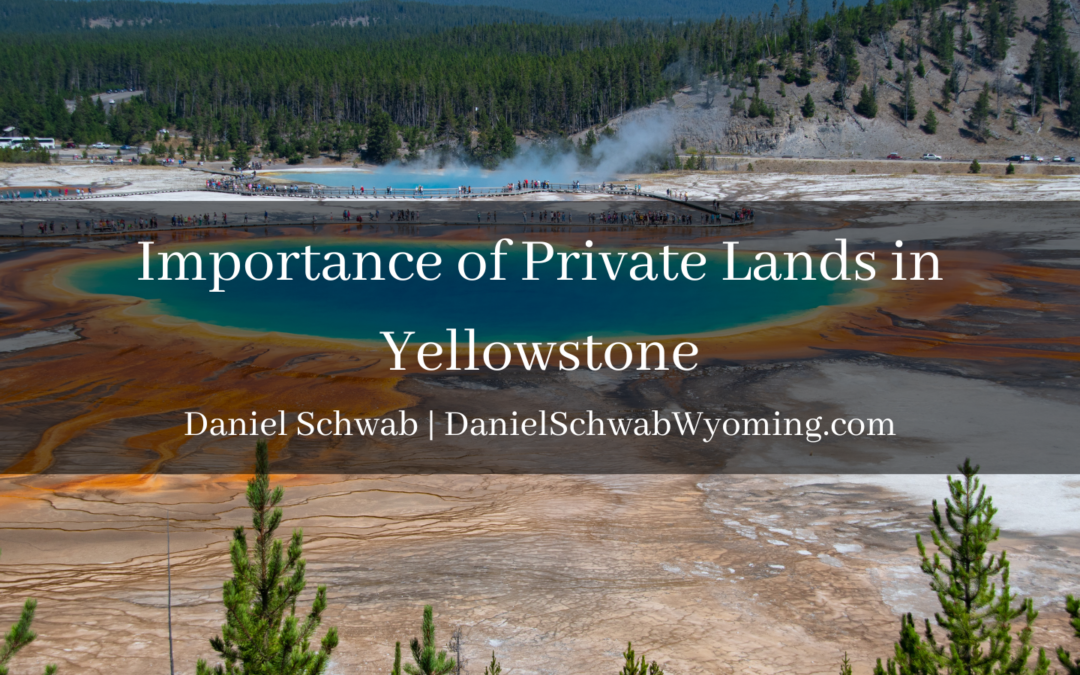

Yellowstone National Park has been an example of American conservation for 150 years. As the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone is celebrated, it reminds us of how far we have come with conservation, as well as where it needs to go next. When the park was established, there was a consensus that it, as well as other similar lands, should be protected. Roosevelt, Pinchot, Muir, and many others constructed this consensus over the decades to follow.

In 1872, the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act was signed. President Grant set aside 2 million acres as the nation’s first national park, but they quickly discovered this was not enough land to protect the wildlife. By 1886, Army General Philip Sheridan, who was also a park manager, was asking Congress to make the park bigger. Although this was rejected, over the next century new national forests, wilderness designations, and state wildlife reserves were established. Hunting and fishing regulations, as well as endangered species protections, helped the wildlife recover from overharvest and persecution. Combined, this protected millions more acreage on top of the land in Yellowstone.

Over the years, ecology and conservation biology were created. These fields provide a new view of parks like Yellowstone and Grand Teton. For example, it was clear that without proper conservation efforts, many species would face extinction due to the lack of habitat. The 2 million acres of Yellowstone and 15 million acres of national forests have proved not enough.

Conserving the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem requires actions far beyond the Park’s abilities. Conservation efforts have been dominated by attempts to increase protections on public land as well as put more land into the public domain.

The 20th century model of conservation has significant limitations. For example, over-reliance on land acquisition, on public land designations, and on regulation of non-federal lands is incapable of successfully meeting the challenges we face today. We must work with states, tribes, and private landowners in order to conserve functional ecosystems across boundaries.

At the University of Wyoming’s 150th Anniversary of Yellowstone Symposium, a keynote speaker recognized the importance of working with people to conserve land in a voluntary and incentive-based manner. Over the last several decades, new tools to protect working lands from development have been created. The goal is the help manage the land in ways that benefit wildlife, clean water, and the climate.

Wildlife migration provides opportunities to take the tools that have been developed and create a collaborative approach to conservation that will forge connections between landowners, tribes, agriculture, forestry and local communities.

Big game migrations demonstrate the old model’s limitations. Native American tribes followed these migrations seasonally. And in the last 20 years, satellite-based GPS tracking has provided insight like never before. By mapping and tracking migrations, we have gained vast knowledge of these patterns and behaviors. For example, we now have information about the path hundreds of pronghorn travel on between the Green River Basin and Grand Teton National Park. As well as the 150-mile journey thousands of mule deer take in Wyoming. We can track elk, mule deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, moose, and bison as they migrate twice a year.

If you follow these migration routes, you end up outside the protected lands and parks. You end up on private land, which makes up about 30%, or 6 million acres, of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. When the United States promoted settlement through land privatization, settlers chose the most productive land.

Wildlife uses the land for the same reasons humans do, which is why creating working relationships with private landowners is so crucial. Partnering with landowners to conserve crucial habitats on private land might have as much impact as what happens within the parks on protected lands.

Active participation from the landowners is necessary when conserving places like the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Ranchers and farmers are knowledgeable about their lands and land stewardship, and they want to help develop solutions. In the GYE, there are ranches that winter hundreds of migratory mule deer, and some that winter four migratory big game species, including 2,000 elk. Some landowners have concerns about elk and brucellosis, predation from wolves or grizzly bears, damage to fences and forage from wintering animals.

As this collaborative model of conservation develops and expands, climate change poses new issues. We need to be flexible and have the ability to work with changing factors as habitats and species are all affected differently. Science has shown that ecosystems respond to climate change in different ways like moving, shrinking, and growing. No two ecosystems are the same, meaning a new model of conservation must be adaptive and dynamic. But luckily, ecology shows us that many wildlife species and ecosystems are resilient when faced with change.

Conservation is a team effort. It has changed and improved over the last 150 years since Yellowstone was established. If we continue to create working relationships with private landowners, it will provide more growth potential.